Once again, he slipped out when no one was looking. It was the time when it was neither day, nor night, the time when a soft, silvery light hung over the city. After the heart attack, they scolded and fussed over him, hid his packets of Wills, served him toast with Nutralite, instead of butter.

On Aarti’s face, he often detected a faint, accusing look, silently asking him why he had caused all this trouble, the wailing siren of the Mritunjoy 108 ambulance racing through the city streets that June night, eight months ago, the whispers, sobs, the waiting and prayers.

Now, Probir had gotten into the habit of coming into this room straight after work and asking him in a stern voice, “Baba, I hope everything is OK?” Gayatri bought him a book on cardiac health, written by an American heart specialist. It had pictures of pink, smiling men and women running on the beach, nibbling on bowls of chopped lettuce and sitting cross-legged on yoga mats.

His daughter-in-law believed this was just the thing he needed to be motivated to stay alive. Aarti, Probir and Gayatri believed they were doing the right thing to keep him alive. What he hated most was that it no longer mattered to them how he felt. As long as his heart beat regularly, his kidneys, liver, prostrate, intestines, lungs functioned as efficiently as could be expected of a person his age, Aarti, Probir and Gayatri could live out their lives without concern. They were doing everything to keep him alive. Aarti rose every morning, took her bath, and smeared the parting of her white hair with vermilion, daring death to take him away from her. Looking at that red streak, and that gentle accusation in her eyes, he felt impatient, desperate to break free, willing his heart to falter, to ache, to stop. The doctor said he could take his regular evening walks, but not strain himself. The three were horrified. What if he got a second heart attack on the street? So, they sent him out with Maloti, the maid. Maloti walked after him, humming to herself, flinging stones at dogs, cheerily calling out to other maids in the nearby houses. She so annoyed him that one evening, he came back and flung a tea cup across the dining room. No more walks, Probir’s eyes bored into his through the thick lenses. When had this son become his father? Then they gave up on him. Every evening, he slipped out of home, unhitched the front gate and made his way along the lane.

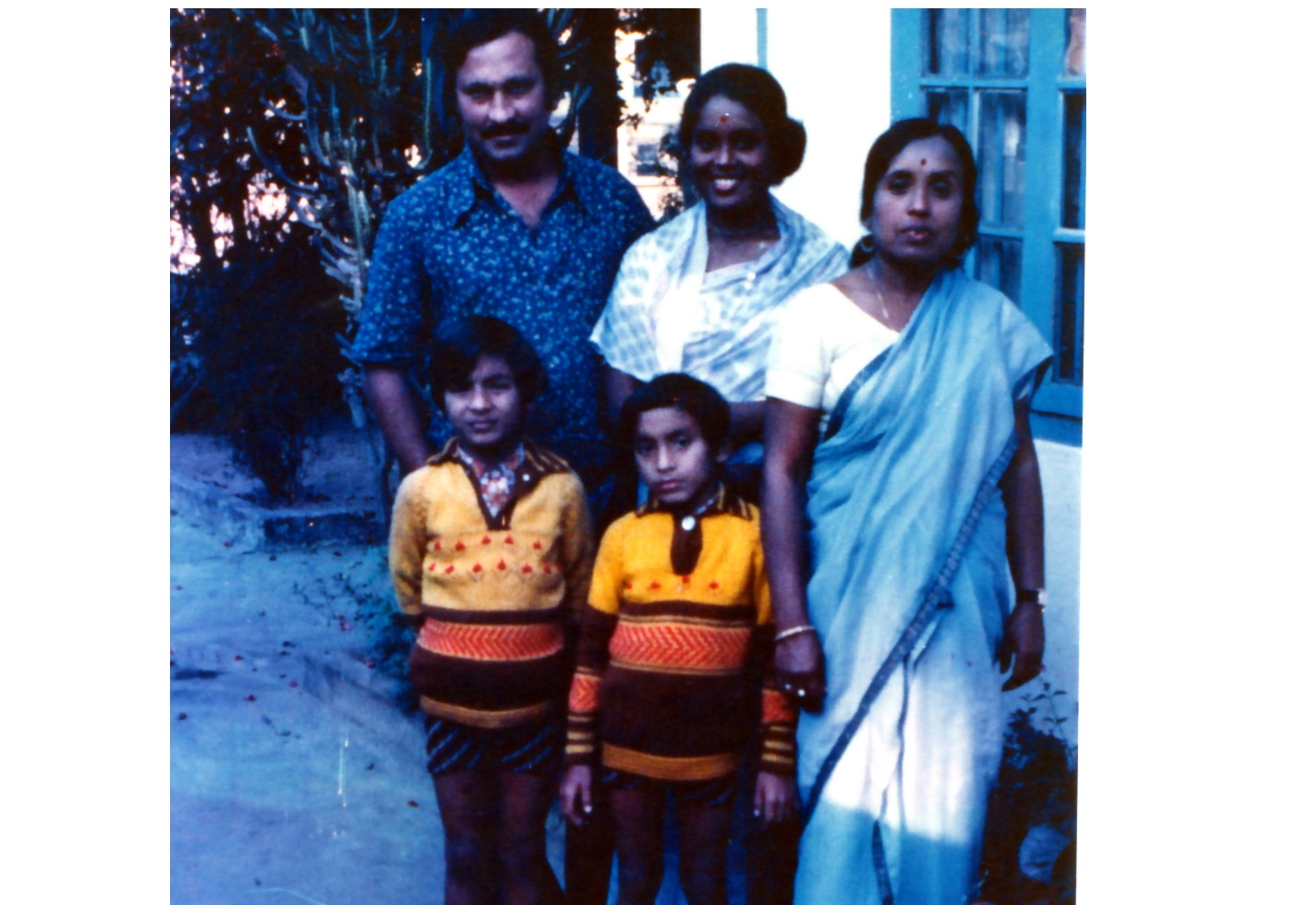

He no longer remembered the names of his neighbours. Every evening’s walk was meant to keep his heart working, but to him, it was always more than that. In the street, nobody reminded him that he was damaged goods. Cars hooted impatiently for him to spring aside. No one reached out to steady him when he stumbled. He liked to stand by the railway tracks and watch the trains thundering past, bearing people, oil, coal, sacks of grain, machinery, logs of wood. And after the last bogie rattled away, he gingerly crossed the tracks, tapping the stones with his cane, and on the other end he always stepped at Gopal’s paan shop for a Wills. Inhaling deeply, and feeling the smoke curl out of his nostrils, he felt something had been set right, as if the hands of an old clock were moving again. Eight months ago, when he was close to death, hooked up to the ventilator at the hospital, the city’s four newspapers and three magazines sent their reporters to cover his eventual death. For he was not just another old man. He was Jyotirmoy Chowdhury, the Sahitya Akademi Award winning author of eight novels, seven collections of short stories, two books on criticism. Showed visuals of his hassled family, and the closed door of the ICU, and through the first three days of the crisis, sombre men and women sat in television studios, discussing his themes of angst and alienation, the deliberately flawed nature of his characters, his powers of narrative and his place in the literary firmament. People came to his home, and took away rare photographs, even samples of his handwriting. One magazine brought out a special issue on him, even though he did not die as per their expectations, or even hope. When he came back from the hospital, Probir showed him the magazine, thinking it would cheer him up. But Jyotirmoy Chowdhury felt abused and demeaned. A sourness seemed to fill his mouth. Reading the glowing, laudatory pieces, he felt that his life was one big lie, that his work was trivial, commonplace. What had he discovered about this world that others had not known before? Why were his characters so petty, so mean and helpless in the face of great odds? He buried the magazine in the bottom drawer of his study table. From then on, which was eight months ago, he could not write a line without feeling like an imposter. He knew then that God, or fate, or the blind immanent will that ran the universe, had taken away his life as a writer and now, he was only an old man with a bad heart, waiting his turn to go.

But, there had to be something he was yet to discover. He was sure of it. Everyday, when he stepped out to walk, or puff at a Wills, he wanted to return home with an experience that would make his pen flow, and his mind quicken at the infinite possibilities of life. That evening, he was thinking these thoughts, when a woman touched him on the arm. “Why have you stopped writing?” She was a young woman, with a round, tranquil face. He paused and looked at her. “Excuse me,” he said, “Do I know you?” “What do you think?” her eyes glittered like marbles. “After all that I have been through, because you think you can do anything you like...” “I’m sorry. I must go.” He quickened his step, his walking stick beating a tattoo on the sidewalk. She followed him, talking to him, her words flowing like a dark tide towards him. Five minutes later, she stopped following him. Then a twelve-year-old boy, one side of his face horribly disfigured, clasped his left hand and walked alongside, whistling cheerfully. Then, a man in orange robes and an enormous trident stopped him and smeared his forehead with ash. Something that had gagged and silenced him in these eighth months loosened, and he felt free. Words and sentences formed unbidden in his mind and he felt the old excitement of expressing his view of the world. This was what had made him leave his house at dusk every evening. For the truth came to him on the street, a truth so momentous that it stunned him with its enormity. The moon faced woman was a character in his second novel. The boy with the hideous face was Pandu, son of a tea labourer. He had breathed life into them, given them features, a certain way of speaking, flaws, virtues. He had given them their destinies... Urmila, selling herself to feed her child, Pandu, scarred for a crime he did not commit... the holy man was the thug who changed guises. He had had absolute control over their lives, and they were now coming back to him in the real world.

He felt a delicious fear prickle at the back of his neck. He hurried home, over the railway tracks, the uneven stones, the narrow bylane. Pandu was still holding his hand and when he looked back, he saw the shadowy form of Urmila, the soft slap slap of her sandals on the road. He unlatched the gate, and stumbled up the steps, panting, pushing the boy away. They were all watching television – Arati, Gayatri, Probir. He went to them, sitting heavily on the couch. Maloti brought him a cup of tea and two cream cracker biscuits. He spent the rest of the evening waiting for the knock on the door.