The woman should never have come. But she did, and there is nothing I can do about it.

It happened 17 years ago. Just a night of staying over. Even her name fills me with unease. Sandhya, dusk. Shadows melting from grey to black, a vagueness in which nothing is clearly visible, or what it seems. It is not something I have ever brought up before Utpal. Maybe he is certain I do not remember. I should pretend I don’t. Maybe he remembers, maybe not. Maybe it does not matter. We have, after all, had a good life together.

Pratik is now eighteen, away from home, in a Delhi College. We are alone, together, bound to each other by memories, our child, the sense of journeying together along the long vista of years. Everything in this home is how I want it to be. Among the crystal and ceramic curios is an African couple, an elongated, wooden pair, a man and woman, with shaven heads and slender limbs. They are clad in dull, ochre tribal costumes painted into their ebony bodies. I always place them side by side, looking out at the world, a close phalanx, ranked solidly against crouching lions, famine, forest fires. Isn’t that how it is supposed to be?

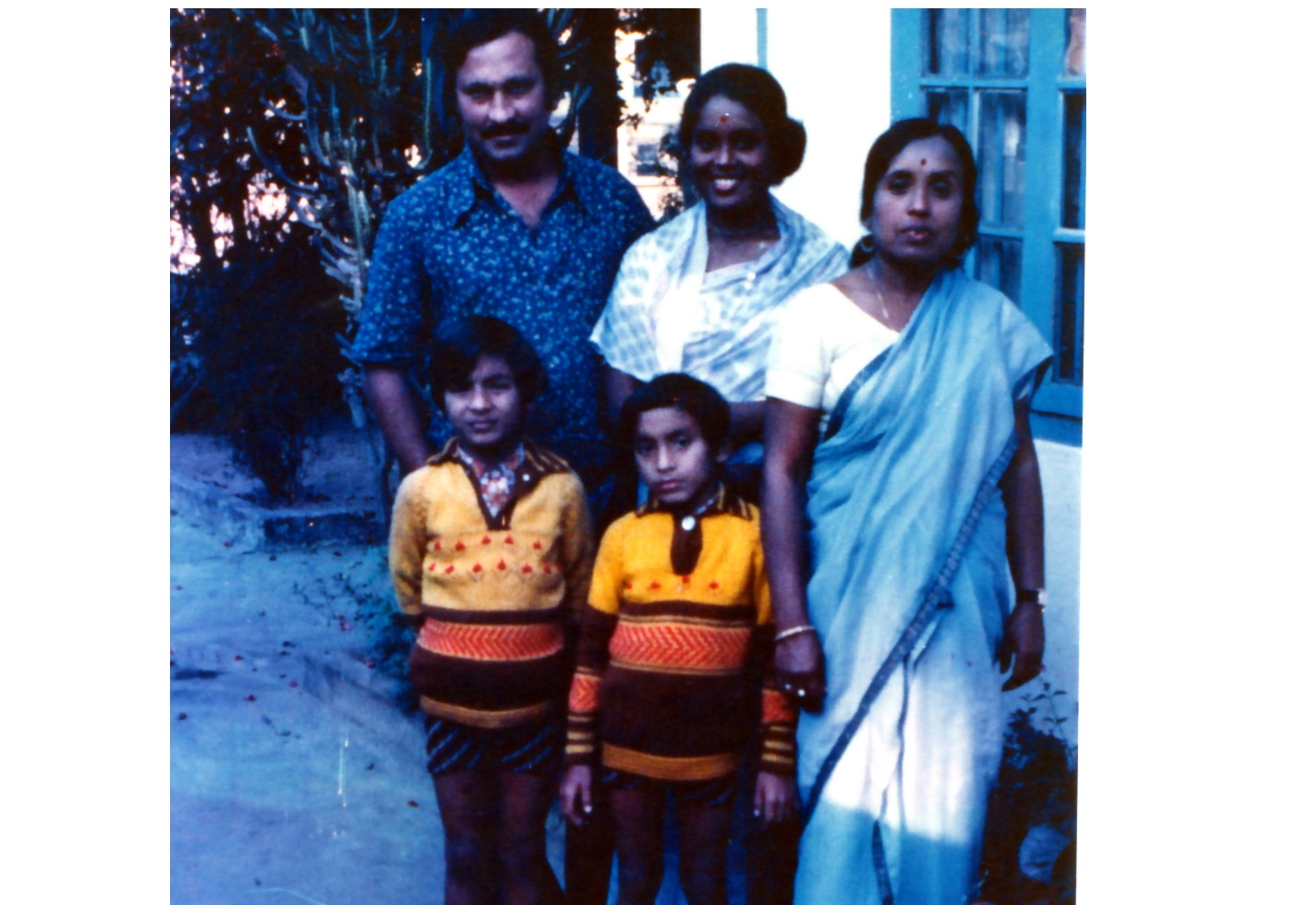

The woman should never have come. She had arrived like a letter that had not been expected, bearing an unfamiliar postmark, awakening that tiny pang of uncertainty, a little frisson of fear I still cannot explain. And instead of me letting her into my home, it was she, Sandhya who opened the door for me that long ago twilight. There must be some meaning in that, something I don’t want to look closely. That was what my mother used to say. What you don’t know cannot hurt you. So, I stood there holding Pratik, seven months old, asleep, a trail of his saliva on my collarbone. I could feel my breasts engorged with milk and my sandals hurting, my sari crumpled. After three hours at the doctor’s, all I wanted was to give my baby his fever medicine and lie down. I knew Utpal was home. He would insist I rest. But when I rang our doorbell, a stranger I had never met, a woman answered. She stood against the soft, diffused glow of the living room lamplight, looking at me, a polite smile of puzzled inquiry on her face. It’s alright. Utpal came up behind her. This is Suravi, my wife. Suravi, this is Sandhya here. Remember Arun, my friend, the journalist at Frontier Times? Sandhya is his sister. She’s going to stay here tonight. Just some problem. Missed the night bus to Tinsukia. Here, give him to me. What did the doctor say? Utpal and I go to our room. On the way I notice two cups of tea on the tray. Whether he had made the tea or she had offered to do so, it is the same thing. In my short, three-hour absence, a woman has made herself at home. The woman should never have come. But because she had, I changed my mind about lying down in my cotton polka dotted nightie, my face wiped clean of make-up, suckling our infant son. Sandhya was slender, her oval face framed by a mass of curly, almost frizzy hair. Her tweezed brows arched over her dark, watchful eyes. A single bracelet circled one pale, delicate wrist. The white silk sari with the black paisley motif suited her, even gave her a touch of class. If she had worn crimson nail polish, splotches of ruby red on the tips of her long fingers, I could have found it easier to know what kind of woman she was. But her nails neatly clipped, unvarnished, gave nothing away.

I could not understand why, as Sandhya flipped through the Feminas in our living room, something changed in the way I felt about myself. I saw myself through her eyes – a young wife, a mother. Mid-twenties, pretty, but letting herself go. The wads of fat on her back, the dark circles because the baby cried in the night. A woman slipping into complacence without even knowing she was. And when I saw what she showed me, I felt bloated and ugly, I felt betrayed by the long scar on my abdomen, the furrowed, puckered stretch of flesh and skin stitched up by a masked surgeon seven months ago, the scar that made Utpal flinch, turn off the light. The woman should never have come. I remember brushing my hair seated on the dressing table, leaving it open, changing into the pink sari he once said I looked good in. Utpal was in no hurry to explain why he had been so kind to the sister of his boyhood friend. He spooned the antibiotic solution into Pratik’s mouth, Pratik cried and he dandled him on his knee, crooning the baby language that we were learning to use. I listened, intently, so that I could detect if he was trying too hard to be normal, to be too sincere about being a good father. But he was calm, undistracted, as if he was completely at ease about the presence of this sudden guest in our house. This woman should never have come. In my English Honours class, I had read of women who were feared by other women – Madam Bovary, forsaking everything for love, Anna Karenina, dying in its quest.

In the life I have built with Utpal, my college sweetheart, I want the small, safe pleasures of a well-cooked meal, a weekend matinee show, and drifting to sleep in the dreamlike contentment of our once-a-week unhurried love making, I want the right to buy shirts for Utpal, and to scold him when he goes beyond four cigarettes a day. Even Pratik is the name I chose, Pratik - a symbol. A symbol we wrought out of our love, this fragile thing we started in a college corridor, with a teasing question, lowered eyes, frantic notes between books – now a whole home, three rooms, sofas, beds, dressing mirror, cabinets, wardrobes, cutlery, books, stuffed toys, albums of memories, two lives becoming one. And a bright, plump baby with a dimpled bottom who already follows us with his eyes. But there is always a but. In trying to become one, I shed my differentness, layer by layer, shrinking, so I could fit into the idea, the idea of who I thought I should be, for my man, my son. And it was this diminished me that Sandhya saw when she first held the door open and wordlessly, with only her raised eyebrow and polite, disinterested smile, made me face the colourless, insipid matron I had become. The woman should never have come. If she hadn’t, I would have just warmed the leftovers and put the rice on the cooker. Now a meal had to be cooked. The part-time maid did not come at night. I am in my new pink sari, my hair open, taking the chicken out of the freezer and she comes in. I am really so sorry for all the trouble, she says. She stands near the dining table. Is the baby sleeping? Good, good. Listen, I’m not really hungry. I had something in the evening. I’m a light eater. No, no trouble. We have to eat as well. I put the chicken on the rack to thaw. She sits on the chair by the table and waits for me to give her a task. I put it off as long as I can, rebuffing her. But it is almost nine and Utpal has a company meeting at ten tomorrow. Pratik could wake up and cry any moment. I wash three potatoes, put them in a pan, include the peeler, and push it across the table. Here, just skin them. But you must change your sari. Did Utpal show you the spare bedroom? Don’t worry about me. She starts scraping a potato. I can adjust. Are you sure you don’t want me to slice the onions. Someone taught me to slice onions inside a bowl of water. She gives a small laugh. That’s how you can avoid those tears... So, you missed the bus? I am boiling the dal in a wok, and slicing beans to fry; Yes, I reached the station late. There wasn’t a single seat. And where were you planning to go? Oh, Jorhat, my mother lives there. In another wok, the oil is heating up. Blue smoke drifts across the kitchen as the Paanch phoron crackles. The sliced onion, bay leaves, the slit chilli go in, sizzling. I pour the dal over it. There is an angry roar as liquid meets fire. It bubbles and I turn to pick up the chopped coriander leaves. My tone is level, very conversational. But I thought Utpal said Tinsukia, you were going to Tinsukia. She never misses a beat. Did he? He must have heard me wrong. I said Jorhat. I work at the Tocklai Experimental Station. I’m a stenographer there. Oh, Utpal must have thought I’m going to visit my mother. Our home is in Tinsukia. But you wouldn’t know that. We haven’t ever met. Utpal says the only way to eat chicken is fried. I have my own magic with ginger paste, fresh coriander, diced onions and hot and sweet sauce.

Tonight, it seems so important to make Utpal happy. The pieces of meat sizzle on the pan. I stir them and watch her. I know your brother Jayanta, I say. He comes whenever he is here. He’s wife’s a Bengali, isn’t she, I can’t seem to remember his Calcutta address... Golf Links... Ballygunge? She gives no sign of hearing my question. The potatoes are done. Do you want me to set the table? Should I take out the water bottles from the fridge. She is restless, covering up our silences with offers of help. There is a lovely aroma filling the kitchen, something sweet, hot and fragrant. I am in the middle of something I have created, something with which to bind Utpal to me, on this dark, unsettling night, when a strange woman with her snake-like eyes sits in the heart of my home and spins a web of lies. Utpal comes in, holding a thermometer. Just a sec, Urvi. Come and hold Baba, I want to take his temperature. Don’t forget to switch off the gas. In our room, he lifts our sleeping baby from the cot. I hold him, unbuttoning his shirt so Utpal can place the thermometer under his armpit. We wait. Seconds pass. The fever is down this body is cool. I put him back on the cot, carefully arranging the mosquito net. Listen, don’t ask her anything about Jayanta. Utpal’s voice is low. Jayanta and she have had some fight. I don’t know the details. No, they stopped talking two years back. Don’t know... But she missed the bus and needed help. I’ve known her for so many years. It’s not safe for a woman at night. No hotel would let in a single woman... I’m going to take the blanket and extra pillows to the spare room, I say and walk away.

Utpal is not a good liar. He did not sound convincing. There must have been a reason why a brother would not talk to his own sister. It would be something she had done. Something dirty and wicked and unspeakable. Something that Utpal knew about but wanted to leave unsaid to honour his best friend, to avoid upsetting me, adding to my post partum blues. But most of all, the reason that I feared – to protect her from my censure, to hide from me what she really was, not because I would be shocked, but that I would never let her in through the door should she wish to come in some distant, unforeseeable future. The woman should never have come. A man and a woman have dinner together that night. Utpal helps himself to the rice, the woman serves the dal, pouring it delicately over his mound of white, steaming rice. They talk quietly as they eat. I will never ever know what they were talking about. I was in our bedroom-as Pratik pulled at my teats, gasping between each frantic gulp, I could feel myself flow away in the darkness, silently straining to hear the faint murmur of their voices in the dining table. Even after all these years, Sandhya’s image comes back to me, - the Sandhya Utpal must have been looking at as he tore with his teeth the flesh of the chicken pieces - a slender woman in black and white, a dark halo of frizzy hair, a single gold bangle on the fragile wrist, and such dark, knowing eyes. I do not remember if I ate at all that night, after Pratik slept. I do not remember if she left after breakfast the next day, or before. All I remember is that she had no luggage when she left, only her black handbag with the silver clasp. That woman should never have come. She came for a night, and has been with me for a lifetime. But because she came, I understood – with a sharp pang, how much I loved my gentle, good-natured young husband and how fiercely ready I was to clasp him to me, to fight for this life we had made together. Sandhya was the darkness through which I saw the lighted window of my small, perfect world. She alone has helped me understand that, and for that, I must remember her.